As vaccination rates rise and regulations lift, we find ourselves at a crossroads in the history of the traditional workplace. The pandemic ushered in the age of remote work almost overnight, and for the last fifteen months companies and employees alike have been forced to adjust.

Throughout the pandemic, 70% of full-time workers in the United States are working from home (Owl Labs Survey). Now, companies are faced with a decision– allow employees to continue the work from home (“WFH”) lifestyle they have grown accustomed to, or to ask them to return to the office. At this unprecedented juncture, it serves to look analytically at the costs and benefits of working from home. Who benefits most? Who loses out? Is remote work the most efficient model moving forward?

Let’s take a look.

The Positives

There are clear benefits to the work from home model, for both employers and employees.

For employees, time saved is money saved. According to Owl Labs, employees saved an average of 40 minutes daily by not commuting. Some of us in the Los Angeles area, where MAP is located, probably saved considerably more time than that. The time collectively saved gives workers more time for themselves– time that can be spent on hobbies or devoted to physical or mental health.

Owl Labs also reported that freedom from commuting allowed workers to save around $500 a month, resulting in savings close to $6000 a year.

Certainly spurred in part by the freed time and saved cost, multiple studies have shown that worker productivity rises in a work from home scenario. A Stanford study of 16,000 workers over 9 months showed that work from home increased employee productivity by 13%. These workers reported higher satisfaction, and their attrition rate halved during these nine months.

As hard as companies have tried in recent years to move their offices beyond the fluorescent-lit seas of cubicles that recall the film Office Space, a majority have found the home environment preferable– if a bit lonely: the study reported that “being alone had some negative effects on willingness to work from home, but the quietness had positive effects on productivity.”1

With worker satisfaction and overall productivity both increased in WFH scenarios, the question becomes: what’s the catch?

The Negatives

When thinking about the future of work, we have to think about work collectively. The benefits of working from home are simply unattainable for many vital professions. Most medical professionals cannot work from home. Public servants cannot work from home. Construction and maintenance workers cannot work from home. Manufacturing workers cannot work from home. Most of these are blue-collar workers and all these professions provide trades, crafts, and services that quite literally hold up our economy and infrastructure. Thus, anyone who can work from home benefits from services provided by those who cannot.

So, while the ability to do your job from your computer is more prevalent than ever, we must acknowledge that it is far from uniform across the professional world. We must look at the conditions that enable work from home and their socioeconomic implications.

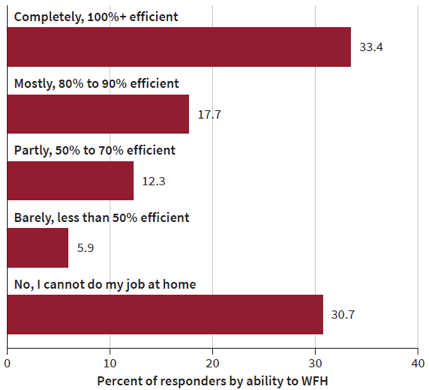

A June 2020 study by Stanford’s Institute for Economic Policy Research2 broke down the WFH applicability of the survey responder’s jobs (figure 1).

If two thirds of jobs are not fully WFH-enabled, and almost another third are fully incompatible with it, we cannot assess working from home as “the future of work.” Such a view skews far too heavily towards certain types of jobs– often at the cost of blue collar, front line jobs our economy depends upon.

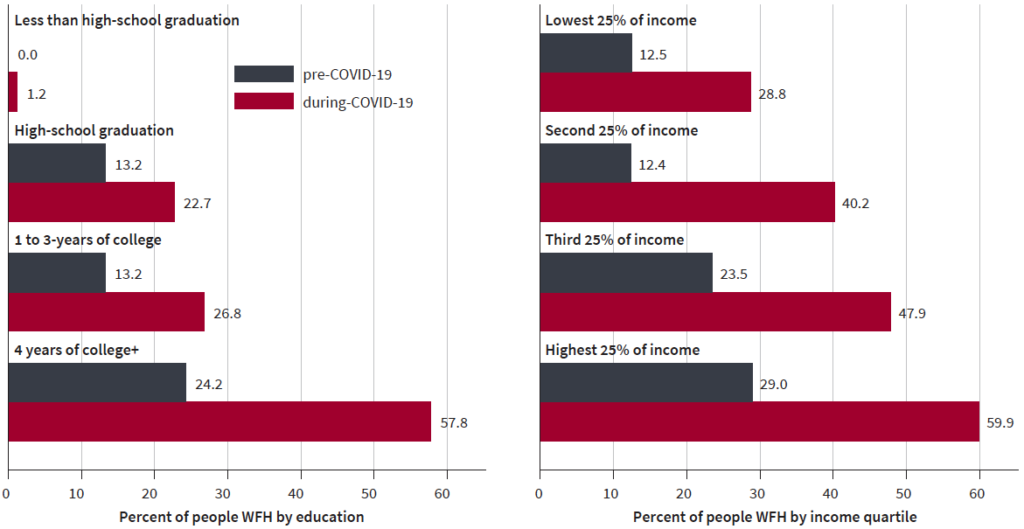

This, of course, represents a stark socioeconomic divide. The same Stanford study showed that the ability to successfully work from home often indicated a higher education level, as well as a higher income percentile (figure 2).

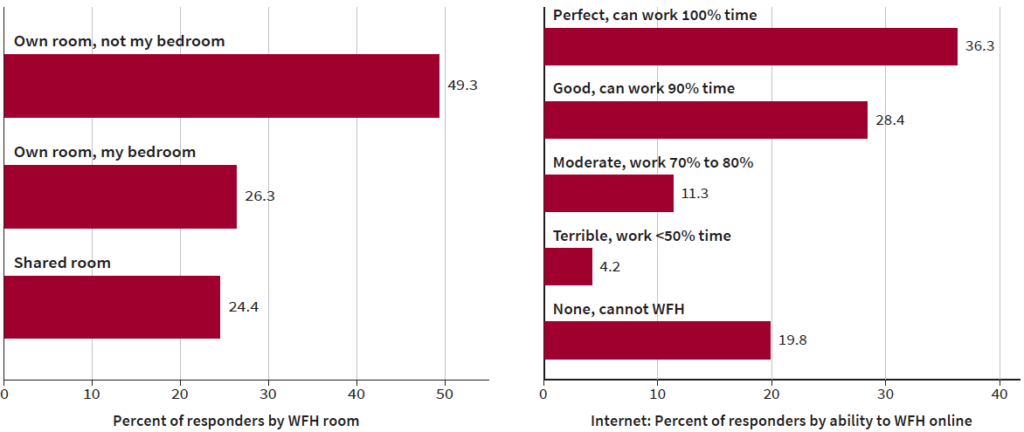

The socioeconomic divide exposed by WFH widens when we look at facilities and internet access. Responders to Stanford’s survey showed that only 49% of workers have a room other than their bedroom to perform their roles. Only about two-thirds of responders reported having strong enough internet connection to perform their role from home (figure 3).

The Takeaway

So, as much as we hear of WFH as a seismic shift in the habits and lifestyles of our workforce, we must look at it as a stark portrait of the dichotomy between what “work” means for the rich and what it means for the poor.

Lower income workers, by and large, cannot afford to work from home. Or, their role might make it impossible. They may not have strong enough internet, or their homes might not be a work-conducive environment. For these workers, the time and money spent commuting will not diminish. The daily grind will continue– all while WFH-enabled workers continue to benefit from the fruits of their labor.

Lower income workers, who also tend to have longer commutes, would certainly stand to benefit from time and money saved on their commutes, which tend to be longer than those of higher earners. They would benefit from the mental health benefits reported by those who transitioned to WFH.

Thus, as we continue into the remote age, let us be aware that the transition to remote work is not a democratization of work. It does not benefit everyone, as many proponents say that it does.

By exposing this clear socioeconomic rift, the remote age offers us a clear call to action to improve flexibility, accessibility, and benefits to the hands-on, blue collar, frontline workers upon whom we so often depend.